In a historic moment in June 1934, the Indian National Congress, for the first time, officially demanded an Indian Constituent Assembly1 to frame India’s Constitution. This added a new strand to Congress’s political engagement with the British on the future of India. Going forward, the demand for a Constituent Assembly would be made alongside calls for ‘Purna Swaraj’ or complete independence.

The Congress’s demand was triggered by the 1933 British White Paper2 that emerged from the Round Table Conferences. These conferences were organized with the aim of resolving India’s constitutional and communal issues. However, when the conferences failed to produce satisfactory results, the British government drafted a ‘White Paper’ outlining a range of constitutional reforms for India.

The White Paper faced significant criticism and opposition from Indian political parties, including the Congress. They argued that the proposed reforms did not adequately address India’s aspirations for self-governance and were insufficient in granting Indians the right to determine their own constitutional future.

On 16-17 June 1934, the Congress Working Committee passed a resolution which stated that the White Paper ‘in no way expresses the will of the people of India…the only satisfactory alternative…is constitution drawn up by a Constituent Assembly elected on the basis of adult suffrage or as near it as possible, with the power, if necessary, to the important minorities to have their representative elected exclusively by the electors belonging to such minorities’

This was first time that the Congress officially demanded a Constituent Assembly for India. The British ignored the demand and embarked on a process to implement the White Paper. With every move that the British made, the Congress reiterated, with even greater force and conviction, its demand for a Constituent Assembly.

The British government’s next step was to refer the White Paper to a Joint Committee set up by the two houses of British parliament. The Committee was tasked to prepare a report. When this Report came out, the Congress termed it as a document that aimed to ‘facilitate and perpetuate the domination and exploitation of this country’.

The report formed the basis on the Government of India Act that British Parliament passed in 1935. The Government of India Act 1935 was in effect going to be the Constitution of India. The Congress rejected the Act and in a 1936 resolution declared that ‘no constitution imposed by outside authority and no constitution which curtails the sovereignty of the people of India and does not recognise their right to shape and control fully their political and economic future can be accepted. ‘

The resolution went on to say that the only Constitution that was acceptable was one that was based ‘on the independence of India as a nation and it can only be framed by a Constituent Assembly elected on adult franchise or a franchise which approximates to it as nearly as possible.’ The Resolution once again demanded ‘in the name of the people’ for a Constituent Assembly.

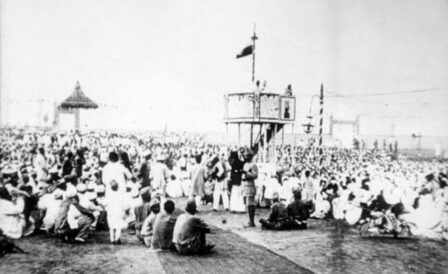

In the same year, Jawaharlal Nehru, in his presidential address at the Faizapur Congress, told the gathering that the demand for a Constituent Assembly was now the ‘cornerstone of Congress policy today’. And indeed, it was. Resolution after resolution, speech after speech, the Congress kept re-iterating its call for a Constituent Assembly.

Towards the end of the 1930s, the Congress had more or less managed to saturate Indian political discourse with the demand for a Constituent Assembly. Around the same time, the Second World war was on the horizon, and the British saw the cooperation of Indians as critical in the war effort. The British could not ignore Indian political demands anymore. In August 1940, through a statement made by Viceroy Linlithgow – ‘August Offer 1940’ – it recognised the right of Indians to frame their own Constitution. While this was a victory of a sort, the ‘communal problem’ now took centre stage: the Muslim League had passed the Pakistan Resolution earlier in the year triggering a widespread uncertainty and conflict among India’s political parties. The formation of an Indian Constituent Assembly was still a distant possibility.

More blog posts

Our Independence Movement Constitution

26 January 2025 • By Editorial Team

What made the Indian Independence Movement so unique? How did the experiences of the Independence movement leaders shape the framing of our Constitution?

Bhagat Singh Hanged, Karachi Resolution Passed

23 March 2023 • By Vineeth Krishna

On 23 March 1931 the British hanged Bhagat Singh for his involvement in the Lahore Conspiracy Case. Just a week later, the the Indian National Congress passed the iconic Karachi Resolution 1931. Were these two historic events connected?