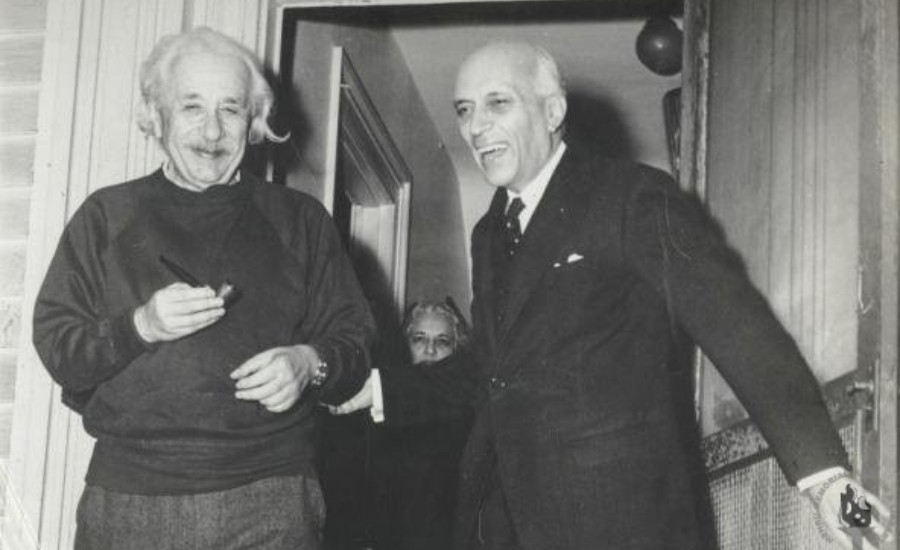

“May I share with you the profound emotion I experienced upon learning recently that the Indian Constituent Assembly has abolished untouchability?” began Einstein’s letter to India’s interim Government Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Dated June 13, 1947, it was written to Nehru six months into the drafting of India’s Constitution. While Einstein’s sentiment may very well have been genuine, the letter aimed to use it as a segue into a matter that Einstein wanted Nehru to take a position on.

As the Indian Constituent Assembly worked towards transforming India into a constitutional republic, significant global events unfolded concurrently. The aftermath of World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust dominated international consciousness. This period also witnessed a surge in discussions about the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, fuelled by the atrocities committed against the Jewish population in Europe and the escalating conflict between Jews and Arabs over the idea of an Israeli State.

In the midst of these global developments, India grappled with the decision of whether to support or oppose the creation of Israel. Indian political leaders had adopted a strategy of refraining from taking a definitive position. While acknowledging the Jewish community’s rightful claim to justice after the persecution in Germany and historical injustice, they simultaneously underscored the importance of recognizing the rights of Arabs to inhabit their lands.

Einstein’s letter was a an attempt to sway Nehru towards endorsing the idea of an Israeli state, and he did so through three types of arguments. First, he suggested an equivalence between the Jews and the untouchables, subtly aligning the Indian struggle for freedom with the movement to establish a Jewish state:

“… I read that the curse of the pariah was about to be lifted from millions of Hindus in the very days when the attention of the world was fixed on the problem of another group of human beings who, like the untouchables, have been the victims of persecution and discrimination for centuries…”

Second, Einstein appealed to Nehru’s internationalist credentials, emphasizing global justice and equality as compelling reasons to support the Israeli state. He positioned himself as a like-minded advocate for morality in international relations, attempting to forge a shared commitment with Nehru.

Third, Einstein portrayed the transformative economic impact of Jewish contributions to Palestine, emphasizing that this transformation did not stem from exploited labor through traditional capitalist means. Instead, it arose from the economic revitalization of the land, fostering economic equality and a burgeoning trade union movement—all achieved through the hard work and creativity of the Jewish people.

Nehru, was not impressed.

A month later, Nehru responded to Einstein with measured tact and firmness. While acknowledging Einstein’s sentiments regarding the Indian Constituent Assembly’s decision to abolish untouchability, he deftly avoided equating the struggles of the Jews with those of the untouchables. Instead, Nehru chose to articulate a broader notion, asserting that all oppressed people deserve justice, and that he genuinely sympathized with the tribulations faced by the Jewish community.

Nehru’s response to Einstein’s suggestion that a Jewish state would promote international justice was realist and blunt:

“…As you know, national policies are unfortunately essentially selfish. Each country thinks of its own interests first and then considers others. If an international policy aligns with the national policy, then the nation employs lofty language about international betterment. However, as soon as that international policy appears to clash with national interests or selfishness, a host of reasons are found to justify not adhering to that international policy…”

In response to Einstein’s economic argument, Nehru’s retort was even more pointed. “After all these remarkable achievements,” Nehru asked Einstein,

“..why have the Jews in Palestine failed to gain the goodwill of the Arabs? Why do they seek to compel the Arabs to submit against their will to certain demands? The approach taken has not led to a settlement but rather to the perpetuation of the conflict. I have no doubt that the fault is not confined to one party but that all have erred…”

This sharp query revealed Nehru’s skepticism towards an economic argument that bore historical echoes of justifications of colonial and imperial rule.

Throughout the rest of the letter, Nehru remained resolute in his refusal to adopt a definitive position on the Israel question. Einstein’s attempt to influence Nehru , intricate as it was, ultimately fell short. In retrospect, this exchange between Einstein and Nehru serves as a captivating historical snapshot, capturing the convergence of global events, moral imperatives, and the intricate political maneuvering at the time when India would soon transform into a republic.