This article first appeared on the Pluralist Agreement and Constitutional Transformation (PACT) website. ConstitutionofIndia.net is a part of the PACT project an international collaboration that aims to generate new scholarship and impact activities around Indian constitution making.

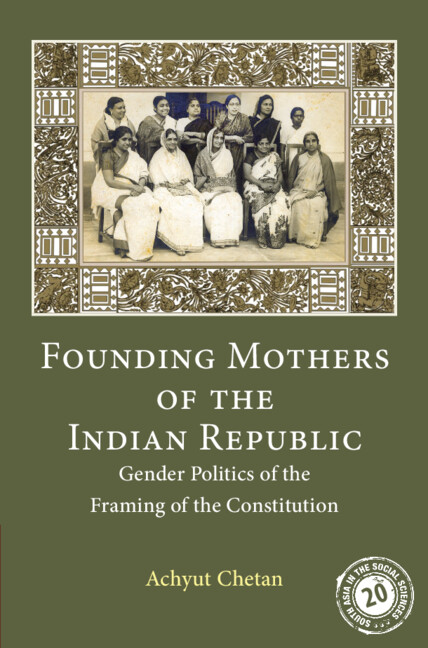

Achyut Chetan’s new book Founding Mothers of the Indian Republic: Gender Politics of the Framing of the Constitution, remembers the women members of the Constituent Assembly and sheds light on their contributions to the making of the Constitution. The drafting of India’s Constitution has been the subject of a range of academic and popular writing in recent years. However, this book is arguably the first substantive engagement with the role of women in India’s constitutional founding.

The focus on women members that Achyut brings in his work highlights the astute approach that the women members brought to the drafting process, building on their strengths with an awareness of what approaches would not yield the desired results in terms of their campaigns for women’s rights, for instance. This ranged from the preference to put forth their proposals for constitutional provisions and drafting choices by making submissions in writing as opposed to interventions in the plenary debates, building on their work at the All India Women’s Congress (AIWC). Women members also prioritised choosing to get their foot in the door and settling for the acceptance of watered down versions of their demands that could later be expanded upon, as opposed to the rejection of lofty demands that would shut the door on their proposals with finality.

Women members also stood out in their affinity for collaboration, with women speaking on behalf of each other, for instance, Amrit Kaur standing in and contributing for Hansa Mehta when she was unable to be present in the Constituent Assembly due to her work in the United Nations. They were also conscious of the differential treatment given to contributions made in the drafting process, depending on which member made the contribution. Women members thus took to writing letters to influential male members of the Assembly to have their proposals put forth and given due weight. Such collaboration as a feminist strategy as a mode of constitutional debate and drafting is a sharp and much needed addition to the strategies of conflict, consensus, arguing and bargaining that often dominate the study of constitutional drafting processes.

Another key contribution that Achyut brings through his work is the careful and nuanced reading of the demands and propositions of the women members, highlighting the dynamic nature of their positions on issues pertaining to the ‘woman question’, and their staunch commitment to equality and rights for women. Achyut offers evidence of their ever evolving demands that ultimately culminated in what now stands as Article 15(3) of the Constitution of India, as a recognition of the additional social disabilities faced by women and the need for the state to rectify these disabilities, with minority status being seen as a result of social disabilities and not biological difference. Dakshayani Velayudhan’s position on the unsuitability of granting women night shifts despite arguing for the right to work for women shows a nuanced understanding of the harassment due to the indirect discrimination women would face through such a formal equality approach. This substantive equality approach can be seen in the contribution of women drafters to issues pertaining not just to the ‘woman question’, especially evident in the robust protections argued for under procedural fairness which are now reflected in Articles 21 and 22 of the Indian Constitution.

Although Achyut’s work is unique and profound, not all of his arguments are fully convincing. Although the need for women drafters to anchor their demand to the nationalist movement is understood, I cannot help but wonder what was sacrificed or lost in such a strategy. The notions of substantive equality, though present and firm, are often defeated by other claims made by women, raising the need to inquire further into the eliteness and the radicality of the women members, just as a matter of due diligence and not of disagreement or rejection of their contributions. Another aspect to engage with critically is phrasing. Achyut deliberately and consciously chooses the phrase Founding Mothers, to refer to women drafters in order to counteract the gravitas of the phrase ‘Founding Fathers’ and to elevate the women drafters to their rightful, and equal, status. However, the phrasing of ‘Founding Mothers’ paints a picture of motherhood that cannot be seen to be as an appropriate corollary to fatherhood, especially in the context of constitutional drafting and the pedestal that men in the drafting committee are often placed on.

The book serves as a provocation to making similar inquiries into the presence and contribution of women drafters in issues beyond rights and the ‘woman question’, perhaps inquiring into the form of parliament, judicial functioning and the executive that was enshrined in the constitution. It might be useful to broaden the evaluation of women’s contributions to constitution-making, not merely by assessing whether their proposals ended up in the Constitution or not. We could examine their participation in debates and discussions, as well as their dissenting views during committee and plenary stages. The question to be asked is, what was the impact of these eleven women on the Constitution of India? What would the Constitution look like if there were no women in the Constituent Assembly?