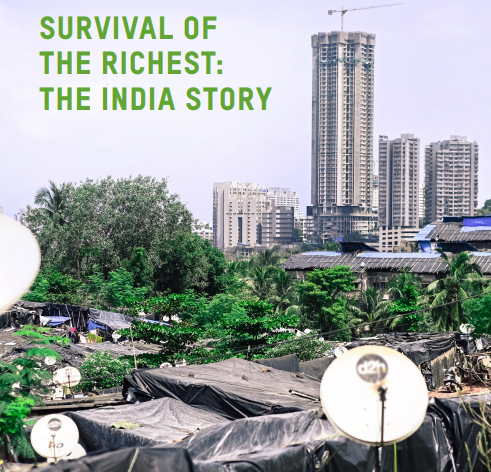

The gap between India’s rich and poor continues to grow at an alarming rate. A recent report by Oxfam India, a non-governmental organisation committed to ending discrimination confirms this worrying trend. The report relies on data publicly available from the Union Government along with other economic data available from institutions like Forbes and Credit Suisse.

Image Credits: OxfamIndia

The report finds that the concentration of wealth among the top 5% of the Indian population has increased to more than 60% of the total wealth in India. The bottom 50%, however, possess only 3% of India’s wealth, a number that has steadily decreased between 2012-2021. To put it in numbers, according to the report, “The combined wealth of India’s 100 richest has touched $660 billion (INR 54.12 lakh crore) – an amount that could fund the entire Union Budget for more than 18 months.” The report also points to disparities in the amount of tax (in the form of GST) paid by the bottom 50% compared to the top 10%, dispelling the myth that only a small section of income tax paying citizens contributes to the government’s coffers.

This state of affairs falls spectacularly short of our Constitution and its framers’ imagination. The Indian State is tasked by Article 39 to ensure that ‘that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment’.

When Article 39 (Draft Article 31) was being debated in the Constituent Assembly, members were in agreement that the Constitution had to charge the Indian State with the responsibly of not allowing wealth and income to be concentrated in a few hands. However, they did have differing conceptions on the means of achieving this.

For many in the Assembly, wealth and income inequality in India could only be tackled through a socialist lens. The economist KT Shah wanted the Draft Article to outrightly prevent the creation of monopolies in industries. In agreement with him was Shibban Lal Saxena, who wanted it to be explicitly put down that the State shall control a few key industries.

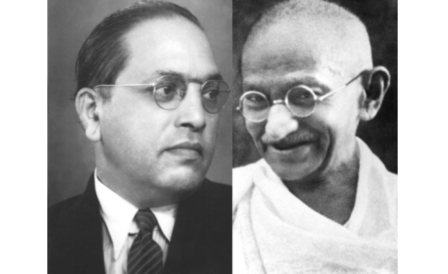

Some members, like Naziruddin Ahmad, were not comfortable with the Constitution endorsing contested political and economic ideologies. Ambedkar assured the Assembly that the language of the Draft Article was composed in such a way was to ensure that it was adaptable to any particular economic model chosen by future Indian governments. In a previous debate, he had argued that the goal of the Directive Principles was to establish the idea of ‘economic democracy’. This could be achieved in multiple ways.

Therefore, the language of Article 39 was crafted to be adaptable to any economic model chosen by future Indian leaders, with the goal of ensuring full economic inclusion for all citizens – which the Indian State has failed in achieving.

Comments

Leave a Reply

More blog posts

How did Ambedkar and Gandhi imagine Indian Federalism?

13 October 2022 • By Vineeth Krishna and Siddharth Jha

B.R. Ambedkar's and M.K. Gandhi's contrasting views on the caste system, have garnered wide attention. Here, we compare their views on an important constitutional design feature: Federalism.

The British Game of Sovereignty

20 December 2022 • By Tanya Kini

The United Kingdom are allowed to field four separate teams in international football. The reason: their unique constitutional arrangement based on devolution of the UK parliament.

Why shouldn’t policy makers propose an index that accounts for not only the GDP but also factors in the ensuing wealth distribution and environmental cost of the growth, to replace the conventional indices of economic growth. Just my loud thinking.