On 1 May, the Supreme Court made significant interventions in the divorce law governed by the Hindu Marriage Act (HMA), utilising its power under Article 142, which enables the courts to issue orders “as is necessary for doing complete justice.” Two key decisions were announced. First, the Court declared its discretionary power to waive the mandatory 6-month cooling period and other procedures for couples seeking divorce by mutual consent. Second, it granted itself the discretionary authority to allow divorce on the grounds of ‘irretrievable breakdown’, even if one spouse opposes it. This landmark ruling expands the range of grounds on which individuals falling within the HMA’s purview can seek divorce.

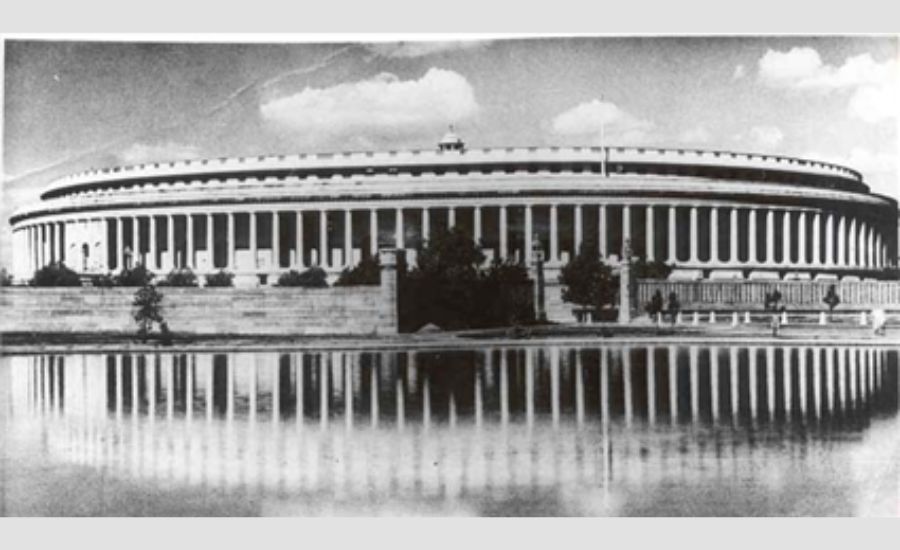

When the Act was originally debated in Parliament in 1954-55, it faced strong opposition from conservative members. Despite the Act introducing a limited set of grounds for divorce, such as adultery and abandonment, Jan Sangh members like U.M. Trivedi argued in the Lok Sabha that Hindu law considers marriage to be an indissoluble sacrament. They feared that introducing divorce would negatively impact the institution of family and destabilize Hindu society.

Female members in the Lok Sabha, including Ammu Swaminathan from the Malabar coast and Bonily Khongmen from the Khasi hills, rejected these arguments. They pointed out that divorces were still rare and that the concerns of conservative members were unfounded. Subhadra Joshi passionately advocated for the limited Bill, emphasising its potential to provide relief to women trapped in abusive marriages.

The majority of members welcomed the Bill and praised its moderate approach to a sensitive topic, leading to its passage. However, a few members expressed their belief that the Bill was too restrictive. Balasaheb Khardekar questioned why two people who no longer wished to be married should be forced to remain so. He framed his arguments in terms of individual liberty and happiness. A. Karunakara Menon had previously presented similar reasoning during the debates on the aborted Hindu Code Bill in 1949, advocating for easier access to divorce.

While these voices were in the minority at the time, subsequent developments have aligned with their vision. In 1976, Parliament amended the Act to allow divorce by mutual consent of the married couple, which encountered little opposition. In 1978, the 71st Law Commission recommended adding ‘irretrievable breakdown’ as a ground for divorce.

The recent Supreme Court judgment also recognizes that divorces have been granted in cases of ‘dead marriages’. By expanding the grounds and procedures for obtaining divorce, we have moved closer to Khardekar and Menon’s perspective, which views marriage not only as a social institution but also as a means for individual fulfillment.

More blog posts

Desk Brief: Did Indians Participate in Constitution Making?

29 March 2022 • By Editorial Team

A paper by Ornit Shani, a political scientist, explores the role of regular Indians in the Indian constitution-making process.