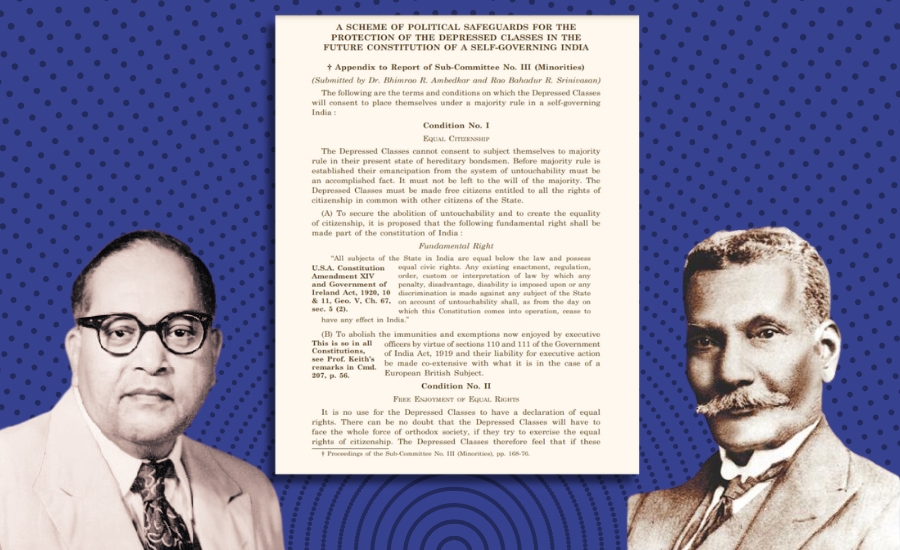

On Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s birth anniversary, we reflect on his critical role in shaping modern India’s constitutional vision. Among his many contributions, the 1930 A Scheme of Political Safeguards for the Protection of the Depressed Classes, co-authored with Rao Bahadur R. Srinivasan and submitted at the First Round Table Conference, deserves far more recognition than it typically receives. This document laid out a strikingly forward-thinking framework for Dalit rights and continues to resonate in contemporary debates around caste, representation, and equality.

The Scheme outlined eight key provisions (‘conditions’) aimed at ensuring the political and social empowerment of the Dalit community. These were not parsed as abstract ideals but aimed building specific legal and institutional safeguards designed to correct centuries of structural marginalisation. Central to the proposal was the demand that the Dalit community be treated as a distinct political entity with guaranteed rights, rather than as a social category passively assimilated into the nationalist project.

The scheme opens with striking clarity and force, setting the tone for what follows:

“The Depressed Classes cannot consent to subject themselves to majority rule in their present state of hereditary bondsmen… The Depressed Classes must be made free citizens entitled to all the rights of citizenship in common with other citizens of the State.”

What follows, then, is a legal provision effectively calling for the abolition of untouchability and the full recognition of members of the Dalit community as equal citizens. This anticipates Article 17 of the Constitution and stands as one of the earliest efforts to link Indian social reform to enforceable legal and constitutional norms in the context of Dalit rights. The scheme makes clear that legal equality alone is insufficient unless supported by affirmative duties on the part of the state—an argument that continues to be central to contemporary constitutional jurisprudence.

Another major concern addressed in the scheme is the practice of social and economic boycotts. The scheme proposed that these forms of coercion be explicitly criminalised, even detailing specific acts that should attract penal sanctions. This foresight anticipates later legislative interventions such as the Protection of Civil Rights Act (1955) and the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (1989). Ambedkar and Srinivasan demonstrate a clear understanding that social exclusion operates not only through overt discrimination but also through informal economic and cultural sanctions. A similar provision was later included in States and Minorities 1947, submitted to the Constituent Assembly, but it too was excluded from the final Constitution—though statutory provisions would eventually address the issue. Ambedkar’s recognition of the widespread nature of this practice was remarkably prescient; even today, social and economic boycotts remain a powerful tool of oppression against marginalised communities. He was among the earliest thinkers to argue that such practices should be explicitly named and tackled through constitutional provisions and the force of law.

In one of its most historically controversial yet crucial provisions, the scheme calls for separate electorates for the Depressed Classes—a demand that would shape much of Ambedkar’s constitutional efforts in the decades to follow. He viewed it as a necessary safeguard to secure genuine political representation, particularly given the entrenched dominance of upper-caste interests in existing political institutions. The demand sparked intense debate, culminating in the Poona Pact of 1932, but its underlying logic remains relevant: without independent political agency, formal inclusion risks becoming mere tokenism.

The scheme called for proportional representation in legislatures, cabinets, and public services. What is noteworthy is the insistence on not only representation but adequate representation—emphasising both quality and quantity. This emphasis prefigures the later policy of reservations, but with a broader focus on structural access to power, not just numerical quotas.

The scheme is also remarkable for its engagement with comparative legal frameworks. It references American civil rights legislation and Burmese laws against social boycotts, showing that Ambedkar and Srinivasan were thinking beyond India’s immediate context. Their approach positions Dalit rights within a broader international discourse on minority protection and democratic equality. In doing so, the scheme not only asserts a claim to justice within India but also aligns that claim with global constitutional developments.

Despite its clarity and foresight, the scheme has remained largely marginal in mainstream constitutional history. This is likely because later documents like States and Minorities received more attention and overshadowed it. Nevertheless, the legal and political vision articulated in the scheme has been quietly absorbed into key features of India’s constitutional framework. Articles 15 and 17, along with the broader system of affirmative action, all bear the imprint of principles first articulated in this early document.

Revisiting the scheme today is not merely a historical exercise. Many of the conditions it addresses—social exclusion, underrepresentation, and legal impunity—persist in different forms. The document reminds us that equality requires more than declarations: it must be structured into the political, legal, and institutional foundations of the state.

In sum, A Scheme of Political Safeguards is one of the earliest and most comprehensive articulations of Dalit constitutionalism. It demonstrates the far-sightedness of Dr Ambedkar’s legal imagination well before the drafting of the Constitution. His insistence on enforceable rights, robust representation, and institutional accountability outline a vision for a radically inclusive democracy. As we mark Dr Ambedkar’s birth anniversary, this scheme invites us to see constitutional democracy not as a finished project but as a continuous struggle—one rooted in the demands first made by those most excluded from power.