The 1945 UK General Election was significant: it came right after World War II. British voters had the chance to shape the post-war future of their war-fatigued country. The two main political parties in contention were the Conservative Party, running on their leadership of the successful war effort, and the Labour Party, which was offering an ambitious social reform programme.

Interestingly, the future of the British empire’s jewel – India – found mention in the manifestos of both parties. The Conservatives stated that ‘..the prowess of the Indian Army [in Britain’s war effort] must not be overlooked in the framing of plans for granting a fuller opportunity to achieve Dominion Status’. Labour told the British people that it aimed ‘to promote…the advancement of India to responsible self-government’.

Both claimed that they would edge India closer to independence. Then again, British public officials had been making similar noises for years, with nothing substantial to show for it. Conservative leader Winston Churchill in many statements indicated less enthusiasm for Indian self-government than what was reflected in his party’s manifesto.

As it happened, Labour won the elections and quickly moved India’s governing machinery to take steps towards Indian independence; it appeared that Labour was serious about its promises for India’s future.

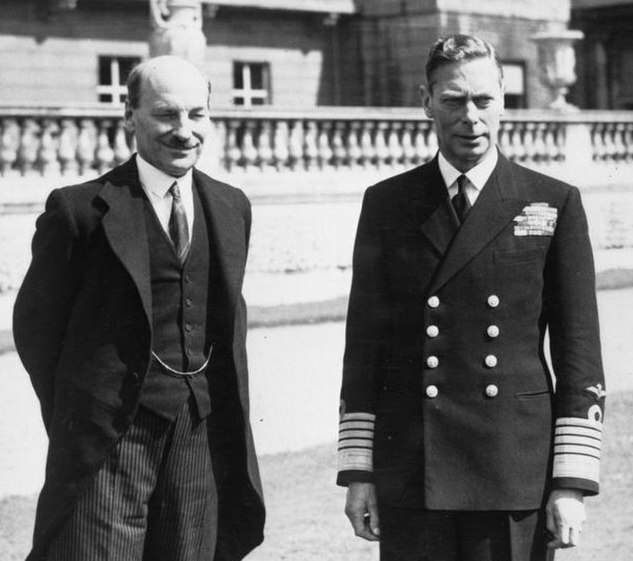

Image Credits: Wikimedia Commons

In September 1945, Viceroy of India, Lord Wavell in a public broadcast announced the Labour government’s new India policy: ‘…His Majesty’s Government are determined to do their utmost to promote in conjunction with the leaders of Indian opinion the early realisation of full self-government in India.’ He continued ‘…It is the intention of His Majesty’s Government to convene as soon as possible a constitution-making body…’

The longstanding demand of the Indian political leaders, first made in the mid-1930s, for a Constituent Assembly manned by Indians, was finally materialising.

But the Viceroy warned:

‘…The task of making and implementing a new Constitution for India is a complex and difficult one, which will require goodwill, co-operation and patience on the part of all concerned. We must first hold elections so that the will of the Indian electorate may be known. It is not possible to undertake any major alteration of the franchise system. This would delay matters for at least two years…’

Image Credits: Wikimedia Commons

These elections would be the basis on which members of the Constituent Assembly would be elected. The limited franchise involved in the selection of the Assembly members is often used as a stick to beat the Assembly’s democratic credentials and legitimacy. However, the adoption of a limited franchise, as the Viceroy suggests, was a decision based on practicality and time, rather than principle.

He went on to mention the ‘delicacy of the minority problem’, which was a proxy for the Muslim League’s demand for a separate state of Pakistan. He threw the ball into the Indians’ court:

‘It is now for Indians to show that they have the wisdom, faith and courage to determine in what way they can best reconcile their differences and how their country can be governed for Indians by Indians.’

The result of the 1945 UK General election and the Viceroy’s speech were triggers for a chain of events, occurring at a maddeningly fast pace, that ended up in the independence of India and Pakistan, and the setting up of two separate constitution-making bodies.