This week, Chileans emphatically shot down a new Constitution. 62% out of the 13 million Chileans who voted in a referendum, rejected the Constitution drafted by a Chilean Constitutional Convention. Although the defeat was predicted by opinion polls leading upto the vote, the startling margin of defeat was not.

The new Constitution was envisioned to replace the old Political Constitution of the Republic of Chile, promulgated by Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship in 1980. A Constitutional Convention comprising 144 directly elected delegates drafted this new Constitution in the wake of the 2019 student protests against increased prices of public transportation. The protests soon broadened into a demand for social and economic reform through a new Constitution. In 2020, Chileans voted to give themselves a new Constitution and a year later they elected members to a Constitutional Convention.

In March 2022, the Convention released a Draft Constitution that soon became the darling of academics and civil society activists the world over. The Draft contained strong protections for the environment, affirmed the right of indigeneous peoples, mandated gender diversity in various public institutions, sexual diversity, set up a national healthcare system, protected the rights of workers amongst a range of other progressive measures. It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that the Draft was the most progressive constitutional text ever written.

But the Chilean people, it appeared, did not share the same enthusiasm. Soon after the Draft was released, opinion polls indicated that Chileans were unimpressed by the new Constitution and approval ratings were dropping. This culminated on September 4, 2022, when they voted No to the new Constitution.

How should we view this rejection of a progressive Constitution? On the face of it, the Chilean constitutional process was designed to succeed at least on paper—the demand for the Constitution emerged from the people, and particularly marginalised groups. The Convention was equally composed of men and women and the Constitution’s provisions catered to all marginalised groups with an impressive bouquet of social and economic welfare provisions.

The Chilean constitutional debacle must be seen with some concern. Future progressive constitutional projects might now be seen with scepticism, mariginalised groups in other parts of the world may lose faith in articulating their demands in a constitutional idiom, and worst of all, dominant social and political elites might now have a reason for stalling constitutional reform.

Considering that public opinion on the new Constitution swerved from enthusiasm to displeasure when the Draft was published, commentators argue that it was the content of the Constitution that put the Chilean people off. Specifically, they point out that the outright imprint of a political ideology, namely the left, was a primary reason. While the people of Chile wanted change, the new Draft was far too radical. Others argue that the failure of the new Constitution was owed to elements of the constitution-making process itself. Or perhaps, it was a rejection of the ruling government manifested itself in the rejection of its new Constitution.

Roberto Gargarella, a Professor at the University of Buenos Aires and the University Torcuato di Tella, has a distinct take on the process. He argues that while the Constitution making project ticked many boxes ‘with delegates who, despite having emerged from a process of high social mobilisation, ended up acting and deciding too far from the society they wanted to speak to’. This argument is persuasive — as most of the delegates in the Convention were independents without much of a political background or pedigree. Perhaps, they fell short of effectively communicating it to the people their vision of the new Constitution and failed to reassure that they were representing the interests of the communities they represent.

Gargarella further broadens the contours of the debate around Chilean constitutional development by problematizing the role of referendums in contemporary world constitutionalism. Referendums only allow only allows for a “yes” or a “no”. A voter who is discontent with one provision of the Constitution, but is in agreement with the rest is limited by the binary options. Voters are forced to reject the Constitution if their partial discontentment far outweighs their general acceptance of the document as a whole.

Further Reading:

The “exit plebiscite” as a constituent error – Roberto Gargarella (Spanish)

What India Can Learn from Chile’s Historic Act of Rewriting Constitution – Nooreen Sarna, The Quint

Rejection of the proposed new Chilean constitution is disappointing – R. Vishwanathan, The Week

Chile’s new draft constitution would shift the country far to the left – The Economist

Chile’s Do-or-Die Referendum – Mary Anastasia O’Grady, Wall Street Journal

More blog posts

The British Game of Sovereignty

20 December 2022 • By Tanya Kini

The United Kingdom are allowed to field four separate teams in international football. The reason: their unique constitutional arrangement based on devolution of the UK parliament.

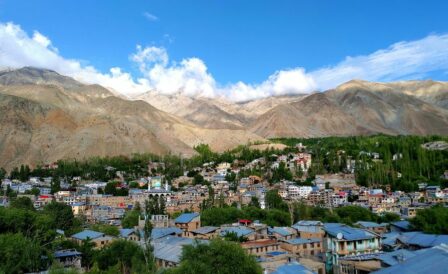

Ladakh’s Sixth Schedule Demand

25 February 2023 • By Varsha Nair

Ladakh has been witnessing huge protests demanding constitutional safeguards for the region under the Sixth Schedule. We examine if this demand is legitimate.