In what is being seen as a significant development towards a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India, the Union Government will present a UCC Bill in Parliament in the monsoon session. This has triggered the latest round of controversy and political tensions which have consistently punctuated India’s post-independence history around the UCC.

The positions taken on the UCC by political and civil society actors can be broadly categorized into three : those who completely oppose it, those who fully support it, and those who support the UCC albeit at an appropriate time and subject to some conditions.

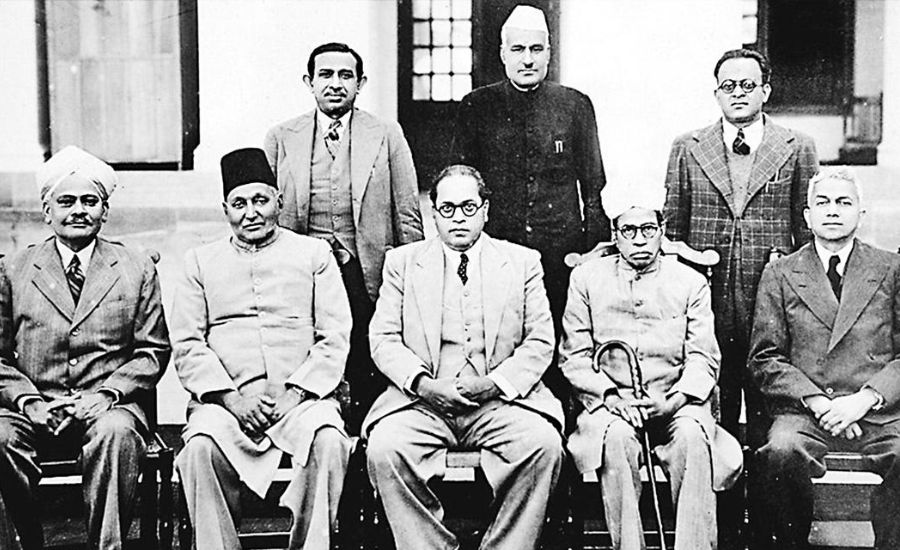

Our Constitution framers belonged to the third category. They desired India to have a UCC, as evidenced by its inclusion in the Constitution, but chose to postpone its implementation for a later time. But why?

Article 35 of the Draft Constitution of India 1948 stated, ‘The State shall endeavor to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.’ On 23 November 1948, when this Draft Article was taken up for discussion in the Constituent Assembly, a series of amendments were moved by Muslim members aiming to effectively bury the article. Ismail Khan was the first to move an amendment and proposed that the UCC would not apply to a community that already had its personal religious laws. Broadly the attacks on the provisions argued that a UCC would violate their freedom of religion, would create disharmony and must not be implemented without the consent of religious communities.

Drafting Committee member K.M. Munshi emerged as the chief defender of the Draft Article. He argued that a UCC was important to uphold the unity of the country and the Constitution’s secular credentials. He reminded Muslim members that this provision would not only affect the Muslim community but also the Hindu community. Further, he emphasized that women’s rights could never be secured without a uniform civil code. The argument that it would violate religious freedom under the Constitution did not make sense to Munshi, as the Constitution allowed for social reform legislation to limit religious freedom.

Pursuing a middle ground, Drafting Committee Chairman B.R. Ambedkar reassured concerned Muslim members that the UCC would not interfere in their personal laws emphasising that it was part of the non-justiciable directive principles of state policy. He proposed that the future parliament could introduce a provision stating that the Code would only apply to those who voluntarily declared their willingness to abide by it.

A week later, during a debate in response to an amendment advocating for the fundamental right to exercise one’s personal law, influential Assembly member Ananthasayanam Ayyanagar reassured the house, stating, ‘There is absolutely nothing in this Constitution that allows the majority to override the minority.’ Ayyangar’s remarks reflected a significant anti-majoritarian perspective, emphasizing the need for cautious implementation of progressive reform provisions in the case of minorities. He emphasized the importance of actively involving minorities, avoiding any perception of a majoritarian agenda.

From the debates, it is evident that the implementation of the UCC was deferred to a later time due to the lack of consent and significant resistance from a particular community. The presence of a considerable power imbalance between the Hindu majority and the Muslim minority in India, and the fear of majoritarianism played a crucial role in the Framers’ decision of defer the UCC. What also surely occupied the minds of the framers was the partition and the precarious situation it placed the Muslim minority in. In such a context, our framers were clear that a UCC could only be implemented when there was a broad consensus, and all minority communities were on board.

The absence of such a consensus was precisely why the 12th Law Commission of India, in its report, recommended against implementing the UCC. However, disregarding these findings, the current government has once again brought the UCC back on the table with apparent renewed vigour. It would be wise for the government to approach the UCC while considering the principles laid out by our framers: obtaining adequate consent and refraining from using their numerical dominance in parliament to forcefully push the UCC into law.